William Mayom Maker

I was born in an isolated village in South Sudan and grew up herding cattle. Caught up in the Second Sudanese Civil War, I underwent multiple transformations. First, I became a guerrilla fighter, then a refugee in East Africa. Finally, I resettled in Canada, where I faced profound culture shock, having grown up in a world without schools, television or hospitals. Yet, after two decades in Canada, I became a degree holder and a published author who works for the government of Canada.

My village was so remote that I didn’t know it was a part of a country called South Sudan. I thought we, the Dinka, were the only people on Earth. Our village had no schools, computers, televisions, or other forms of modernization. Mother Nature was my teacher and classroom, providing me with a multitude of creativity and honing my problem-solving opportunities. I spent time with friends climbing trees, diving in rivers, exploring the grassland and its immense inhabitants, learning about animal food chains and behaviour, and discovering activities to foster my development. My perception of the world changed one day when two strangers visited our village. I was four or five years old, and the strangers terrified me because they looked white and pale, as if they had never seen the sun their entire life. My father referred to the strangers as Kawaja or “white people.” I was scared of these strangers because there was a fairy tale story about lions that turned themselves into human beings and vice versa. And everything about these strangers supported the theory: they didn’t speak Dinka. They looked white and pale because they had turned their skins inside out to conceal the thick fur. Eventually, my parents convinced me that the strangers lived in a faraway country of white people and had come to study our way of life. Their arrival was an omen of my future destiny.

Shortly after that, a civil war erupted between the central Sudanese government and the rebels, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). Gunships, tanks, and troops started bombing villages indiscriminately, killing people and destroying properties. Death and displacement became prevalent, and the once vibrant land looked wretched and completely deserted, with ruins like an ancient graveyard. The SPLA mobilized young boys to train them as fighters. In 1987, I was mobilized, along with thousands of other boys, and marched miles from Sudan to Ethiopia, where we learned guerrilla warfare tactics.

In 1992, the United Nations pressured the SPLA to abandon child soldier practices, so I was disarmed, discharged, and sent to Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya. I languished there for eight years. I was alone and had to rely on my tenacity, courage, and resilience to survive.

In 1999, the government of Canada sponsored me. I came to Canada and faced the advanced world head-on. The child soldier who spent years in the bush, where the only sophisticated thing he knew was an AK-47, now learned how to use a microwave, vacuum, or running water for the first time. My extreme culture shock started on the plane coming to Canada. It was my first plane trip, and I didn't know English. No one had told me the food and beverages served on the plane were free. So, I refused to take any food or water offered during the flight because I had no money.

I landed in Halifax, Nova Scotia. A lady who said she worked for “immigration,” whatever that meant, picked me up from the airport, took me to an apartment, and left. I had lived in mud houses, so the apartment looked like an alien's planet. The only things I recognized in the apartment were a chair, table, and bed. Everything else looked like the alien's possessions. The terrifying thing was a black box with a red indicator and a cord attached to the wall. I had never seen a telephone before, much less used one, so my guerrilla instinct dictated the object could be a bomb. While twenty-three-old Canadians were at colleges learning to be doctors or engineers, this 23-year-old former child soldier was curled up like a frightened turtle in the corner of the apartment, petrified by a mere telephone, thinking it could be a bomb.

The following day, the immigration lady took me to several offices where I received my healthcare card, social insurance number, and other documents. I didn’t know the functions of all these documents yet. Then, we went to the bank to convert my paper money (cheque) into real money. The immigration lady spoke to a smiling young woman at the counter, and I heard my name and “Account.” But instead of giving me money, the young lady, with her invisible friend called Account, handed me a “Debit Card.” I was disappointed and left the bank wondering what the lady with an invisible friend called Account would do with my money.

Settling in my new home was challenging. My inadequate English made me the laughingstock of my peers. My peers, who had not learned a second language, couldn’t understand how hard it could be to learn a new language. I enrolled in an English as a Second Language (ESL) program. I vividly remember failing a pronunciation test because I pronounced “knowledge” as “kah-now-led-ge.” But the same teacher who taught me the 26 letters with their pronunciations now told me some letters were “silent.” That didn’t make any sense to me. Nevertheless, with hard work and dedication, I completed the ESL program and went to college, where I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in business administration, focusing on finance.

After two decades in Canada, the malnourished boy who couldn’t speak English is now the author of two books, The Proud People and Learning the Hard Way, and one anthology, Pearls 35. I am also pursuing graduate studies at Simon Fraser University. Moreover, I am a husband and father of a baby. Lastly, I work for the Government of Canada, giving back to the country that allowed me to rebuild my life. I get great satisfaction knowing I am making a small difference in my new and permanent home.

After walking thousands of miles from Sudan to Ethiopia, I sat among these young recruits, listening to the commander-in-chief, Dr. John Garang, officiating our guerrilla warfare training. In the background are our grass-thatched houses with muddy walls. This was in 1987 and I was 11 years old.

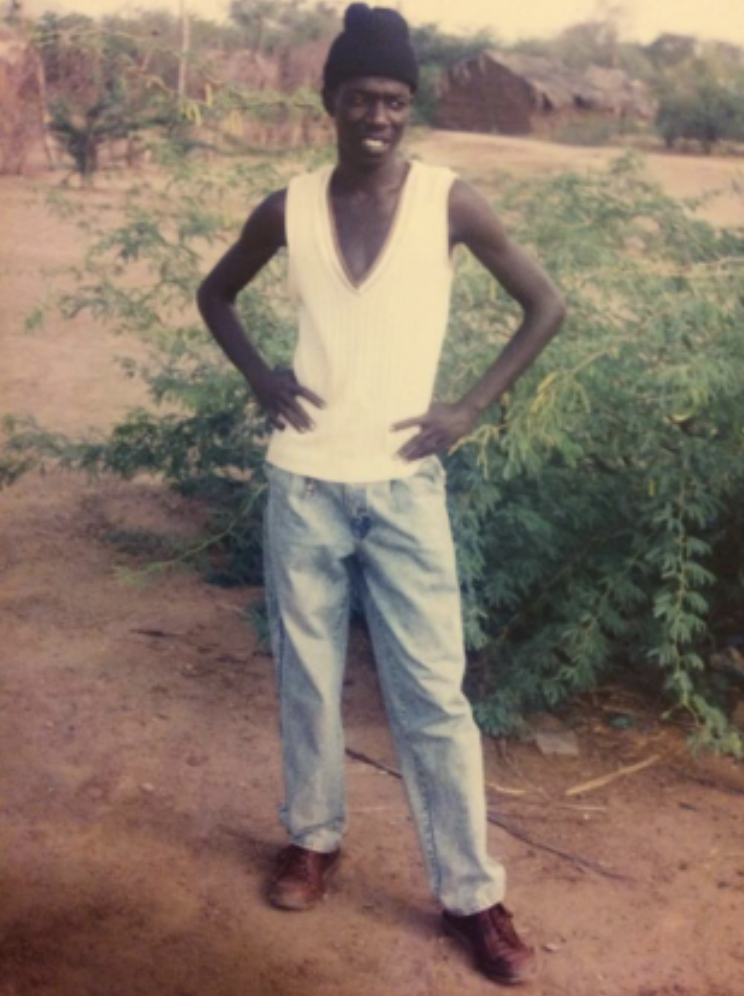

Wearing a black toque and trying to be stylish, I posed for a picture at Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya, in 1992. This was when the UN pressured the SPLA to discontinue child soldier practices, so I was disarmed, discharged, and sent to Kenya.

In 2017, I am sitting with classmates, holding our degrees, ready to take the podium at Douglas College in New Westminster, BC.

Standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the Honourable Tracy Darcy (MLA for New Westminster, BC), I no longer need an AK-47 to make my voice heard—I vote.

In 2023, I finally visited my remote village, where I was born, and found one of my father’s wives with her grandchildren still living there. Our village hasn’t changed much.

My wife, Elizabeth, and son, Mangar, are still in South Sudan, and I am fighting to bring them to Canada.